Home Tags Posts tagged with "cancer cells"

cancer cells

British researchers have made a device that can “smell” bladder cancer in urine samples.

The device uses a sensor to detect gaseous chemicals that are given off if cancer cells are present.

Early trials show the tests gives accurate results more than nine times in 10, its inventors told PLoS One journal.

However, experts say more studies are needed to perfect the test before it can become widely available.

British researchers have made a device that can “smell” bladder cancer in urine samples

Doctors have been searching for ways to spot this cancer at an earlier stage when it is more treatable.

And many have been interested in odors in urine, since past work suggests dogs can be trained to recognize the scent of cancer.

Prof. Chris Probert, from Liverpool University, and Prof. Norman Ratcliffe, of the University of the West of England, say their new device can read cancer smells.

“It reads the gases that chemicals in the urine can give off when the sample is heated,” said Prof. Norman Ratcliffe.

To test their device, they used 98 samples of urine – 24 from men known to have bladder cancer and 74 from men with bladder-related problems but no cancer.

Prof. Chris Probert said the results were very encouraging but added: “We now need to look at larger samples of patients to test the device further before it can be used in hospitals.”

British researchers have explained the way cancers make a chaotic mess of their genetic code in order to thrive.

Cancer cells can differ hugely within a tumor – it helps them develop ways to resist drugs and spread round the body.

A study in the journal Nature showed cells that used up their raw materials became “stressed” and made mistakes copying their genetic code.

Scientists said supplying the cancer with more fuel to grow may actually make it less dangerous.

Most normal cells in the human body contain 46 chromosomes, or bundles of genetic code. However, some cancerous cells can have more than 100 chromosomes.

And the pattern is inconsistent – pick a bunch of neighboring cells and they could each have different chromosome counts.

This diversity helps tumors adapt to become untreatable and colonize new parts of the body. Devising ways of preventing a cancer from becoming diverse is a growing field of research.

Scientists at the Cancer Research UK London Research Institute and the University College London Cancer Institute have been trying to crack how cancers become so diverse in the first place.

It had been thought that when a cancer cell split to create two new cells, the chromosomes were not split evenly between the two.

However, lead researcher Prof. Charles Swanton’s tests on bowel cancer showed “very little evidence” that was the case.

Instead the study showed the problem came from making copies of the cancer’s genetic code.

British researchers have explained the way cancers make a chaotic mess of their genetic code in order to thrive

Cancers are driven to make copies of themselves, however, if cancerous cells run out of the building blocks of their DNA they develop “DNA replication stress”.

The study showed the stress led to errors and tumor diversity.

Prof. Charles Swanton said: “It is like constructing a building without enough bricks or cement for the foundations.

“However, if you can provide the building blocks of DNA you can reduce the replication stress to limit the diversity in tumors, which could be therapeutic.”

He admitted that it “just seems wrong” that providing the fuel for a cancer to grow could be therapeutic.

However, he said this proved that replication stress was the problem and that new tools could be developed to tackle it.

Future studies will investigate whether the same stress causes diversity in other types of tumor.

The research team identified three genes often lost in diverse bowel cancer cells, which were critical for the cancer suffering from DNA replication stress. All were located on one region of chromosome 18.

A new study suggests that chemotherapy can undermine itself by causing a rogue response in healthy cells, which could explain why people become resistant.

The treatment loses effectiveness for a significant number of patients with secondary cancers.

Writing in Nature Medicine, US experts said chemo causes wound-healing cells around tumors to make a protein that helps the cancer resist treatment.

An UK expert said the next step would be to find a way to block this effect.

Around 90% of patients with solid cancers, such as breast, prostate, lung and colon, that spread – metastatic disease – develop resistance to chemotherapy.

A new study suggests that chemotherapy can undermine itself by causing a rogue response in healthy cells, which could explain why people become resistant

Treatment is usually given at intervals, so that the body is not overwhelmed by its toxicity.

But that allows time for tumor cells to recover and develop resistance.

In this study, by researchers at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle looked at fibroblast cells, which normally play a critical role in wound healing and the production of collagen, the main component of connective tissue such as tendons.

But chemotherapy causes DNA damage that causes the fibroblasts to produce up to 30 times more of a protein called WNT16B than they should.

The protein fuels cancer cells to grow and invade surrounding tissue – and to resist chemotherapy.

It was already known that the protein was involved in the development of cancers – but not in treatment resistance.

The researchers hope their findings will help find a way to stop this response, and improve the effectiveness of therapy.

Peter Nelson, who led the research, said: “Cancer therapies are increasingly evolving to be very specific, targeting key molecular engines that drive the cancer rather than more generic vulnerabilities, such as damaging DNA.

“Our findings indicate that the tumor microenvironment also can influence the success or failure of these more precise therapies.”

On January 30, Erivedge (vismodegib) was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat adult patients with basal cell carcinoma, the most frequent type of skin cancer.

Erivedge (vesmodegib) was approved by FDA to treat metastatic basal cell carcinoma.

Genentech (division of Roche) developed the drug in collaboration with Curis. Erivedge will available in pharmacies within one or two weeks. The capsules have to be taken once a day and its safety in children it is unknown.

Patients with locally advanced basal cell cancer who are not candidates for surgery or radiation and patients with metastasis (cancer spread to other parts of the body) may benefit from this medicine.

Erivedge is the first FDA-approved drug for metastatic basal cell carcinoma.

This drug was approved earlier under the FDA’s priority review program for drugs that may offer major advances in treatment.

Erivedge (Vismodegib) inhibits the Hedgehog pathway in the cancer cells.

This pathway is active in most basal cell cancers and only in a few normal tissues (hair follicles).

“Our understanding of molecular pathways involved in cancer, such as the Hedgehog pathway, has enabled the development of targeted drugs for specific diseases. This approach is becoming more common and will potentially allow cancer drugs to be developed more quickly. This is important for patients who will have access to more effective therapies with potentially fewer side effects,” said Richard Pazdur, M.D., director of the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

A clinical study that enrolled 96 patients with locally advanced or metastatic basal cell carcinoma tested the safety and effectiveness of Erivedge.

Researchers recorded the percentage of patients who experienced complete or partial shrinkage or disappearance of the cancerous lesions. In 30% of the patients with metastatic disease a partial response was found and in 43% of the patients with locally advanced disease complete or partial responses were noted. The median progression-free survival rate for both groups was 9.5 months.

Basal cell carcinoma begins in the lower part of top layer of the skin (epidermis) on areas of skin that are exposed to ultraviolet radiation. It is mostly a slow growing and painless form of skin cancer. Most skin cancers appear in older people or in people with an weak immune systems. Every year around 1,000,000 of new cases of skin cancers (aside from melanoma) are diagnosed in U.S. and around 1,000 deaths are recorded.

Important Safety Information for Erivedge

“Erivedge can cause a baby to die before it is born (be stillborn) or cause a baby to have severe birth defects based on how the medicine interacts with the body.

• Female patients who can become pregnant should speak with their healthcare provider about the risks of Erivedge to their unborn child. Their healthcare provider should do a pregnancy test within seven days before they start taking Erivedge to find out if they are pregnant. Women should avoid pregnancy by using highly effective birth control before starting Erivedge, and continue during treatment and for seven months after their last dose. They should tell their healthcare provider right away if they have unprotected sex or think that their birth control has failed. Female patients must tell their healthcare provider right away if they become pregnant or think that they may be pregnant. Pregnant women are encouraged to participate in a program called the Erivedge pregnancy pharmacovigilance program by calling 1-888-835-2555.

• Male patients should always use a condom with a spermicide during sex with female partners while they are taking Erivedge and for two months after their last dose, even if they have had a vasectomy. Male patients should tell their healthcare provider right away if their female partner could be pregnant or thinks she is pregnant while they are taking Erivedge.

• Patients must not donate blood or blood products while they are taking Erivedge and for seven months after their last dose.

• The most common side effects of Erivedge are muscle spasms, hair loss, change in how things taste or loss of taste, weight loss, tiredness, nausea, diarrhea, decreased appetite, constipation, vomiting and joint aches. Another side effect may include missed monthly periods in females who can become pregnant.

• Patients should tell their healthcare provider if they have any side effect that bothers them or that does not go away.

• These are not all the possible side effects of Erivedge. For more information, please see the Full Prescribing Information for Erivedge, including the Boxed WARNING and Medication Guide.”

[googlead tip=”patrat_mediu” aliniat=”stanga”]A new treatment for leukemia had amazing results, surprising even the researchers who designed it. The new treatment has eradicated the cancer cells present in the first three patients tested bodies.

Early results of a clinical trial showed that genetically engineered T cells eradicate leukemia cells and thrive.

Scientists from the University of Pennsylvania have genetically engineered patients’ T cells — a type of white blood cell — to attack cancer cells in advanced cases of a common type of leukemia.

The first two of three patients studied, who received the innovative treatment, have been cancer-free for more than one year. In the case of the third patient, over 70% of cancer cells were removed, according to the researchers.

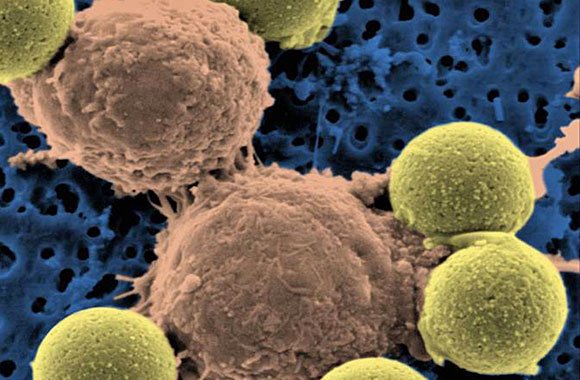

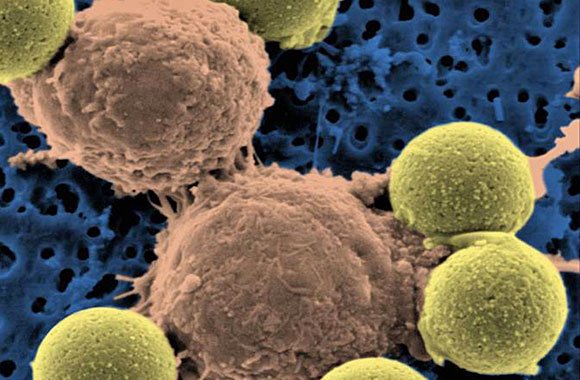

"Microscopic image showing two T cells binding to beads, depicted in yellow, that cause the cells to divide. After the beads are removed, the T cells are infused into cancer patients." (Dr. Carl June / Pennsylvania Medicine)

“In just three weeks, tumors were destroyed, the effect being more violent than we ever have imagined,” said Dr. Carl June, one of the researchers involved in the study.

“Each cell can destroyed thousands of cancer cells,” said June, “each patient have been removed tumors from at least 900 grams.”

“A huge accomplishment”

[googlead tip=”vertical_mare” aliniat=”dreapta”] “This is a huge accomplishment — huge,” said Dr. Lee M. Nadler, dean for clinical and translational research at Harvard Medical School, who discovered the molecule on cancer cells that the Pennsylvania team’s engineered T cells target.

Innovative treatment is using patients’ own T cells, which are extracted from body cells and then genetically modified to attack cancer cells and to multiply and then reintroduced into patients’ blood.

Findings of the trial were reported Wednesday in the New England Journal of Medicine and Science Translational Medicine.

According to LA Times report, for building the cancer-attacking cells, the researchers modified a virus to carry instructions for making a molecule that binds with leukemia cells and directs T cells to kill them. Then they drew blood from three patients who suffered from chronic lymphocytic leukemia and infected their T cells with the virus.

When they infused the blood back into the patients, the engineered T cells successfully eradicated cancer cells, multiplied to more than 1,000 times in number and survived for months. They even produced dormant “memory” T cells that might spring back to life if the cancer was to return.

On average, the team calculated, each engineered T cell eradicated at least 1,000 cancer cells.

Side effects included loss of normal B cells, another type of white blood cell, which are also attacked by the modified T cells, and tumor lysis syndrome, a complication caused by the breakdown of cancer cells.

“We knew [the therapy] could be very potent,” said Dr. David Porter, director of the blood and marrow transplantation program at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia and a coauthor of both papers, which were published in the New England Journal of Medicine and Science Translational Medicine.

“But I don’t think we expected it to be this dramatic on this go-around.”

Bone marrow transplants from healthy donors have been effective in fighting some cancers, including chronic lymphocytic leukemia, but the treatment can cause side effects such as infections, liver and lung damage, even death.

“1/5 of bone marrow transplant recipients may die of complications unrelated to their cancer,” Porter said.

Researchers have been working for many years to develop cancer treatments that leverage a patient’s immune system to kill tumors with much greater precision.

Specialists not involved in the trial said the new discovery is very important because it suggested that T cells could be adapted to destroy a range of cancer cells, including ones of the blood, breast or colon

“It is kind of a holy grail,” said Dr. Gary Schiller, a researcher from UCLA’s Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center who was not involved in the trial.

“It would be great if this could be applied to acute leukemia, where there is a terrible unmet medical need,” UCLA’s Schiller said.

Dr. David Porter added:

“Previously efforts to replace risky bone marrow transplants with such engineered T cells proved disappointing because the cells were unable to multiply or survive in patients.”

“This time, the T cells were more robust because the team added extra instructions to their virus to help the T cells multiply, survive and attack more aggressively.”

“About 15,000 patients are diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia every year. Many can live with the disease for years. Bone marrow transplants are the only treatment that eradicates the cancer.”

[googlead tip=”lista_mare” aliniat=”stanga”]Dr. David Porter cautioned that these were preliminary results and the scientists plan to continue the trial, treating more patients and following them over longer periods.

“The researchers also would like to expand the work to other tumor types and diseases,” Porter said.

The hope, scientists said, is that the method would work for cancers that can kill more ruthlessly and rapidly.